August 18 marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment which opened the franchise to American women. The events that led to this victory constitute one of the greatest advances in American human rights. Generations of suffragists from vastly different backgrounds worked for 80 years to secure national voting rights for women. The suffragists faced endless social and political obstacles, worked tirelessly for decades and risked their lives to ensure that future generations of women could participate as equals in our democracy. These sacrifices and the divisive racial politics that accompanied this struggle must be remembered. It would be both wrong and insulting to suggest that suffrage was achieved as the result of any benevolence on behalf of white men or that the movement was free from racist influence at any point. In spite of the 19th Amendment and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, American men and women of color are still fighting to realize the full measure of their constitutional rights. No American should be content until every citizen can exercise their right to vote freely, easily and safely in any election.

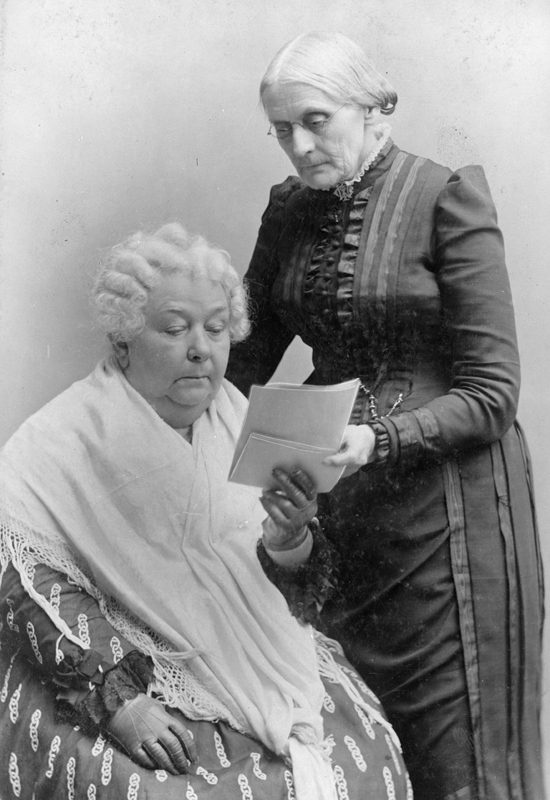

Beginning in 1797, unmarried women and Black men who owned property in New Jersey enjoyed the right to vote. However, in 1807 the franchise was restricted to white tax-paying men only. Between 1840 and 1920 women of every background battled for the right to vote against an intransigent white male establishment. For decades before and after the Civil War, women suffragists such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony challenged Constitutional interpretations in the courts in an attempt to acquire equality under the law. When this failed, Anthony voted illegally, was found guilty and ordered to pay a hefty fine which she refused to pay. Stanton and Anthony founded the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) in 1866 and demanded suffrage in their own newspaper, The Revolution, which bore the motto “Men, their rights, and nothing more; women, their rights, and nothing less.” Nevertheless, in 1869 when long-time ally and abolitionist Frederick Douglass pushed to enfranchise Black men first, Stanton countered with racist rhetoric that disparaged Black men and the AERA was dissolved. Anthony even refused to share a stage with Douglass in later years. This schism plagued the movement at every stage, even as many dedicated white and Black women continued to work both together and separately for voting rights.

By 1913, two powerful opposing factions of overwhelmingly white women had control of the suffrage movement. Their tactical decisions often prevented Black women from sharing the spotlight for fear of losing support among white voters. There was a lot at stake. On March 30, 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment had become law and Black men had been enfranchised. The third and final Reconstruction Amendment to the Constitution was supposed to prevent states from denying a citizen the right to vote based on “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” In practice, it applied only to Black men, and in the South, it had little effect. The infamous Jim Crow laws and lynching in many of the former Confederate states made it impossible for Black men to exercise their rights. Any attempt to broaden or strengthen suffrage was vociferously opposed by the Democratic Party, which thrived on the perpetuation of white supremacy in the Post-Reconstruction South. In the South and elsewhere, some feared that Black women would present more of a threat than Black men, while others saw the potential for white women’s votes to counter votes from Black Americans. In spite of all that white and Black women had done to prove their loyalty to the Union during the Civil War, their contributions and sacrifices went unrewarded. The notion that the franchise should be expanded to include any women divided America right down to the family level.

American suffragist movement entered a new phase after a young Quaker named Alice Paul ventured to England in order to broaden her educational horizons. There she met English suffragists and a like-minded American named Lucy Burns. In 1909, Paul survived incarceration and a hunger strike for taking part in Emmeline Pankhurst’s suffragist campaign. When Paul returned to America in 1912 her reputation proceeded her and the Press was waiting. She signaled to women who were tired of waiting for the full rights of citizenship that she would take up their cause. Paul and Burns joined the National American Women’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and Paul set about planning her first major event as the leader of their Congressional Committee – a parade down Pennsylvania Avenue on the eve of President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. Paul emerged to lead a new generation of women and ignited a suffragist revolution in America. She learned very quickly that soap box oratory on the streets, tea parties for wealthy women or even a short promotional film had no chance of persuading enough men to vote in favor of women’s suffrage.

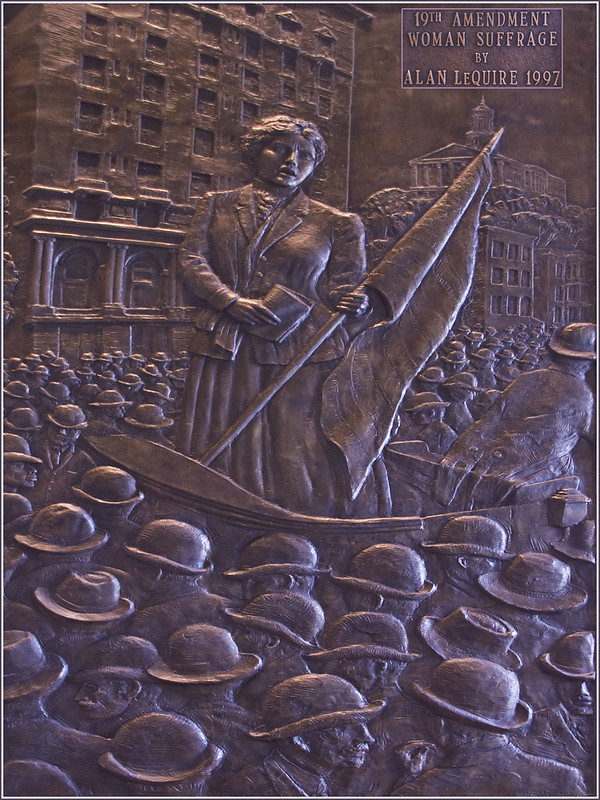

On the afternoon of February 27, 1913 disciplined women 5,000 strong attired in their graduation gowns and work uniforms, adorned in gold, white and purple sashes and carrying banners commenced their peaceful march accompanied by floats and bands. Instead of the warm welcome that 20,000 women had received in New York City the previous year, the suffragists were met by an unruly and largely drunken crowd of about 100,000 men. At first, the bystanders only jeered, but at length they broke through the police lines crushing the procession to single file until the men had surrounded the women. Boy Scouts intervened to protect the suffragists and aided approximately 100 women who had been assaulted. They were finally conveyed to the hospital after the United States Cavalry arrived to quell the mob that the District of Columbia police were unable to control. Meanwhile, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, one of the most prominent Black suffragists and a founding member of the NAACP had arrived with the Illinois contingent. At the last minute, members from her own state insisted she be removed from her prominent place and sent to the rear of the parade, where she would draw less attention. Dismayed, she initially complied but she fearlessly returned to her rightful place when the mayhem ensued.

With the parade behind them, Alice Paul and Lucy Burns formed the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (CU) in April 1913, initially working in concert with the NAWSA. By December, however, it was clear that their goals and methods were incompatible. NAWSA was still the organization of the old pioneers and Paul’s tactics were unacceptable to many of its members. A bitter leadership struggle followed, and in February NAWSA made the split official.

While the struggle for leadership broiled in the East, suffrage had been gaining momentum out West. In January 1915, the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage sponsored a “Freedom Booth” at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. There they started a petition which demanded suffrage for women. It was 18,000 feet long and recorded 500,000 signatures. On September 25, 1915, the journey to deliver the petition to Congress began with a grueling 5,000 mile drive from San Francisco to Washington D.C. Mabel Vernon became ill and retired from the journey in Sacramento, leaving Sara Bard Field and two Swedish volunteers (driver Maria Kindberg and machinist Ingeborg Kindstedt) to traverse the continent in 82 days in an open Willys Overland.

They traveled on the circuitous Lincoln’s Highway — the only viable route at the time. Without gas stations, motels or road maps, the trio motored ahead. On a good day, they were lucky to reach a top speed of 20 mph. Along the way they endured snow, heat and mud before they finally arrived in the nation’s capital on December 6, 1915. With the end in sight, Field decided to ship the precious original petition from Wilmington Delaware to D.C., but the petition never arrived! Thankfully, they had a true, albeit smaller copy of the original. Meanwhile, Vernon had organized a parade escort of 2,000 women for the final march and rejoined the group after making the trip by train. On the same day the House of Representatives heard suffrage amendment proposals from Democrats, Republicans and Socialists. However, at the end of this heroic round none were passed, and President Wilson even refused to mention suffrage in his annual address.

In June 1916, Paul and Burns formed the National Womans Party, which represented a growing number of western states that had voted for suffrage, while the CU carried on representing women in the disenfranchised states. Paul deftly deployed her weekly Suffragist Magazine which was laden with photographs, bold demands and political cartoons. She also effectively courted the Press, correctly predicting that any coverage (good or bad) would ultimately raise awareness and win converts.

Paul adopted the tactics of political prisoners and labor unions that had worked well for Pankhurst in England. Starting on January 10, 1917, the headlines roared that for the first time ever, Americans were picketing outside of the White House gates. For months, about 1,000 “silent sentinels” took turns six days a week enduring bitter cold and harassment during long daytime shifts. They held banners which admonished President Wilson with questions such as “How Long Must Women Wait for Liberty?”

The First World War further split the suffragist movement after America joined the Allies on April 6, 1917. Many women believed that supporting the President in time of war was their first and immediate duty and that suffrage would have to wait. Many of those who did realigned themselves with the NAWSA. Paul and her allies kept up the pressure and insisted that there would be no delay for suffrage or any repeat of the humiliating betrayal that Stanton and Anthony had suffered after the Civil War. Then in June 1917 Paul pressed the point and appeared outside the White House with a large banner proclaiming that America’s failure to enact suffrage made the country a second rate democracy! Moreover, she timed the deployment to coincide with the Russian Ambassador’s visit in order to maximize the President’s embarrassment. Russia, Germany, and the United Kingdom had already acknowledged a woman’s right to vote as a statutory element of her citizenship.

An incensed patriotic crowd defaced the sign almost immediately and a riot ensued. The women were brutally taken into custody and conveyed to jail for “obstructing the sidewalk.” They were charged, found guilty and conveyed to the infamous Occoquan Workhouse prison in Virginia. There Paul and her followers deployed window breaking and other disobedience tactics she had learned in England. However, during the “Night of Terror” on November 14, 1917, the women were chained in stress positions and beaten — some until they lost consciousness. As the campaign continued, subsequent arrests resulted in longer sentences which reached seven months in Paul’s case. She spent a large portion of her time in solitary confinement without mail privileges. Paul and her supporters then went on hunger strike and were ultimately subjected to painful forced feedings. Between November 27 and 28, all of the suffragists were released but not before the public and politicians who had demanded their release were shocked again by the Press coverage of their emaciated figures emerging from imprisonment – several too weak to walk on their own. The public was getting the message. On November 6, just three weeks earlier, 59% of the New York electorate – all men – voted in favor of suffrage.

In spite of Alice Paul’s militant resolve and the effect she had on the American people, she was not the instrument that eventually converted President Wilson, a loyal southern Democrat, into a proponent of suffrage. Did the war change him? Was it the pandemic, the rise of the Republicans, visions of a League of Nations, or something else? While Paul had challenged the President directly, veteran educator and suffragist Carrie Chapman Catt painstakingly cultivated a relationship with Wilson and won him over. After Paul and the CU broke with NAWSA, Catt reluctantly returned as its President in December 1915, in order to bring the crisis under control. However, the timing of the war complicated those goals. A large percentage of the NAWSA membership supported America’s role in the war. Catt pledged that their two million members would break with the pacifists and place themselves at the President’s command to work any job necessary to achieve victory. As the war continued, communication between the President and Catt was constant. Like Paul, Catt also stepped away from Black Women’s clubs and the NAACP whenever the association of the Black vote – men or women – threatened to weaken the movement.

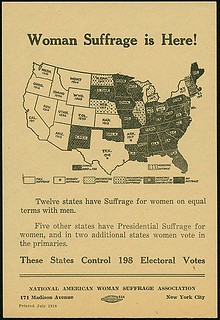

Given the current political landscape, one might imagine that old New England and the West could have provided the needed votes. However, in 1915, New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts and Pennsylvania all rejected women’s suffrage. Their considerable populations and corresponding representation in Congress reduced the available number of pro-suffragist states. Catt won voting rights for women in the western states, only to be crushed in New England. She realized that bypassing adoption by individual states in favor of a constitutional amendment was the only formula that would ultimately secure the franchise. In September 1916, she presented her “Winning Plan” at NAWSA’s convention in Atlantic City, which was designed to secure support from both the federal government and the states outside of the South. To achieve a constitutional amendment, she would need a two-thirds majority from the House, Senate and the States. In order to succeed, Catt’s army needed a new strategy on the ground.

Catt’s NAWSA meticulously recruited women whom they trained to become expert lobbyists. They refashioned the tricks of the political trade from the very men that they ultimately outmaneuvered. They highlighted the potential power of an untapped electorate. Instead of bribes, alcohol, and back room dealings, the suffragist adopted a relentless public “front door” lobbying style. The women always worked in pairs and remained focused on a singular goal which they pursued with unassailable transparency.

In 1869, Wyoming women started voting a full 21 years before the territory became a state. In 1887, the Territory of Montana joined a short list of states and territories that recognized the importance of suffrage. On March 4, 1917, this foundation paved the way for Jeannette Rankin of Montana to be the first woman to take her seat in the House of Representatives. Less than a year later, on January 10, 1918, Rankin introduced the suffrage amendment in the House, where it passed the same day 274 to 136. The required two-thirds majority was exceeded by only a single vote. President Wilson had voiced his support for the amendment on the previous evening, but neither the House vote nor his appeals were sufficient to sway the Senate, which came up one vote short.

1918 was a year like no other. Americans fought hard to break the stalemate of trench warfare in Europe. That summer, they suffered heavy casualties to break the German defenses in historic battles like the one at Belleau Wood. Meanwhile, a largely misinformed American public suffered under the crushing weight of the 1918 Flu Pandemic. Undeterred, the suffragists retained their focus, maintained their grass roots organizations, and continued to apply political pressure. By September 30, fewer than two months before the end of WWI, President Wilson had been fully converted. He delivered a passionate address aimed to break the “unholy alliance” of southern Democrats and New England Republicans in Congress. He urged them to support a suffrage amendment to honor the incalculable contributions that American women had made to the war effort, insisting that they be honored and rewarded with nothing less than equality, justice and the vote.

The 1910 and 1914 midterm elections enjoyed voter turnout of 52% and 50% respectively. But while America was at war and the Spanish Flu raged, that number fell to only 40% in 1918. This decline contributed to a sweeping victory for Republicans, who took back the House and Senate largely on an anti-League of Nations platform. A week later, on the “11th hour on the 11th day of the 11th month,” Germany signed the armistice, and the Great War ended. When the summer of 1919 finally arrived, the pandemic had passed, and the suffrage amendment was once again brought before Congress. On May 21, the House unambiguously passed the 19th Amendment 304-89. On June 4, the newly constituted Senate finally approved it 56-25, sending it to the states for ratification.

With Wilson and Congress onboard, now the calculus of Catt’s master strategy came to bear. Before the amendment could become federal law, 36 states would need to ratify it. This slow and contentious progress began on June 10, 1919, the day that both Michigan and Wisconsin ratified the amendment. As the number of states in favor grew, the southern states closed ranks as predicted. Georgia, Alabama, South Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, Mississippi, Delaware and Louisiana all rejected the amendment in turn. After more than a year, the future of the 19th Amendment fell to Tennessee. A divided state during the Civil War and steeped in racism, Tennessee was one of the last places Catt wanted to risk the final vote. In the week preceding the vote, the anti-suffrage lobbyists poured into Nashville and plied the prohibition-parched congressmen with alcohol from a speakeasy built for the occasion. The Senate ratified the amendment without much fanfare, leaving the final decision to the House. After nine days of contrived procedural delays, the vote finally proceeded on August 18, 1920. By then Catt and her team had all but accepted defeat. Pledges once considered firm had now been compromised, and they feared they would miss the mark by only two votes.

The opposition attempted to table the amendment in hopes of killing it, when inexplicably, 24-year-old Harry T. Burn, who was up for reelection that fall and wearing the red rose of the anti-suffragists on his lapel, voted to keep it alive. His vote resulted in a tie. The exasperated Speaker then called for a vote on the amendment directly. When his time came again, Burn voted in favor, again recreating the tie. At that moment 30-year-old farmer Banks Turner, who had been counted as an anti-suffragist but who had skipped the roll call on the previous vote, announced that he wished to vote aye. His singular vote pushed the 19th Amendment over the line. The State House erupted with jubilation and anger, so much so that Cady Catt could hear the roar from her hotel room across the street. Meanwhile, Burn narrowly escaped through a window in the clerk’s room to briefly circle around and congratulate Turner and the suffragists on the steps of the State House before hastily departing the scene.

What was it that changed young Harry’s mind? In his pocket was a letter which had been delivered while he was in the chamber that morning. It was from Febb Burn, his mother, who had instructed him “to be a good boy and help Mrs. Catt.” The following day Burn explained that he “believed in full suffrage as a right.” He said, “I know that a mother’s advice is always the safest for her boy to follow … .” A few months later he was narrowly reelected after a fierce campaign. He remained in politics for many years. Had Burn and Turner not summoned their courage, American women may have endured a second world war before the franchise was guaranteed by the Constitution of the United States. French women suffered that precise indignity until 1945.

As we approach a pivotal election, millions of Americans are questioning whether their votes will ultimately count this November. Will the pandemic and the current The Postal Service change the outcome at a time when people of color are still facing obstacles to vote? In 1920, only 9 million of the eligible 26 million enfranchised women cast their first votes for President. Three years later, Alice Paul authored the Equal Rights Amendment, which has yet to be ratified by all of the states. With so much won and so much more remaining to accomplish, the employee owners of Sun Light & Power urge you to do whatever it takes to ensure that your vote counts this year – it just might change history.

Seamas Brennan is Marketing Coordinator at Sun Light & Power.